Policy context

Administrative policy

| Authors: | Eleni Briassoulis, Alexandros Kandelapas |

| Coordinating authors: | Constantinos Kosmas, Ruta Landgrebe, Sandra Nauman |

| Editors: | Alexandros Kandelapas, Jane Brandt |

Editor's note 3Jul14: Sources D142-3 and D242-4.

The object and goals of administrative policy are mandated by two general constitutional objectives:

- Effective administration of the state (art. 101)

- Democratic legitimisation of public administration structures at all levels (art. 102)

Policy actors and instruments have been constantly shifting following administrative reforms in 1974, 1986, 1994, 1997, and 2010 following successive (re)formulations of the competences of the branches of public administration, as well as their geographical scope. Administrative reforms are also associated with the evolution of EU structural funds management and the also continuous shifting of those (parallel) structures.

Policy procedures and instruments generally vary (and shift) according to sectoral policy. Horizontal instruments may be institutional (e.g. Statute of Internal Services, Code of Municipalities, licensing procedures) or financial (e.g. national, regional, prefectural, municipal budgets, EU regional aid). Planning instruments are mainly associated with national, regional or sectoral programming documents associated with EU agricultural/structural funds distribution. It is important to note that, despite devolution in competence since the 1990s, the central government has tried to maintain control over both public revenue and spending, resulting in chronic financial dependency of local, prefectural and regional governments. In addition, the small size of local governments as well as the bureaucracy of regional funds has led to a general underperformance of local authorities in mobilizing funds, despite their general availability.

While the division of powers between levels of self-government has been clearly defined, the same has not been the case between elected and appointed authorities at the regional level. This has been a constant source of friction within regions.

Since the 1980s, civil service evaluation, inspection and control mechanisms have been extremely weak. This has often led to underperformance and corruption which, coupled with political favoritism and clientelism, has led to institutional weakness of self-government at all levels. Despite legal and institutional provisions, overall performance of the civil sector by general admission is quite low. Much has been written with regard to the lack of incentives, the general practical impunity of civil sector employees, and political interference (especially with regard to environmental law). Whatever the cause, administrative change, training, and capacity building is generally slow. The civil service (both local and central) has more often been used and regulated as an instrument of political power, rather than as a means of providing effective public services.

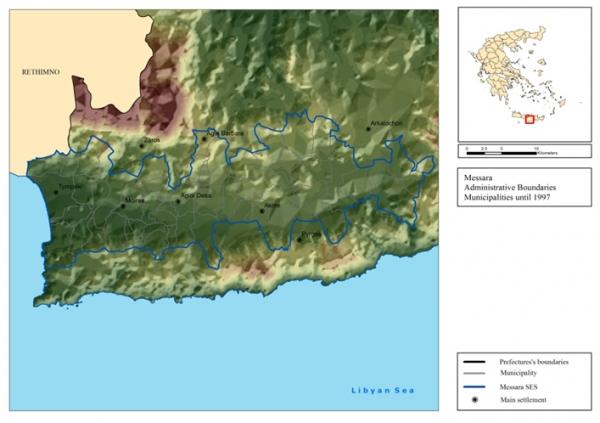

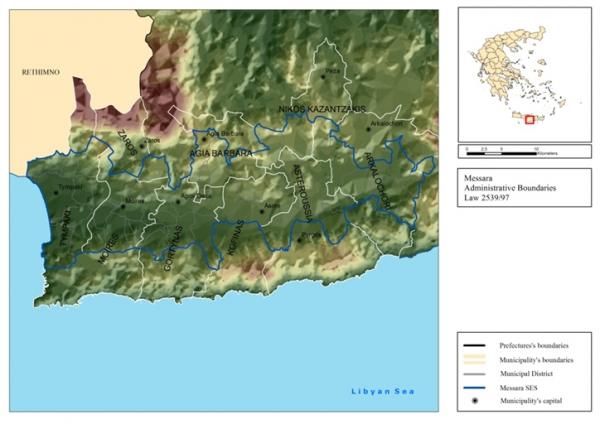

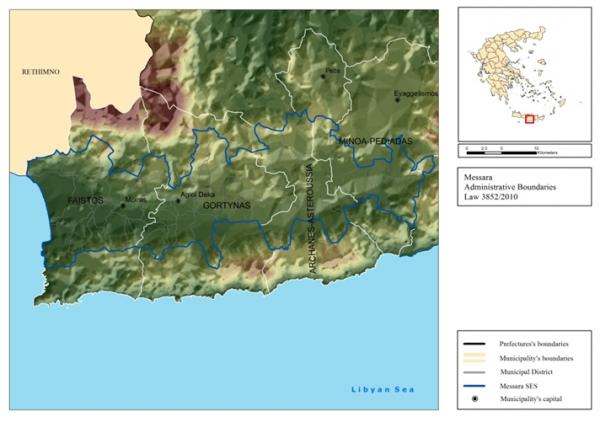

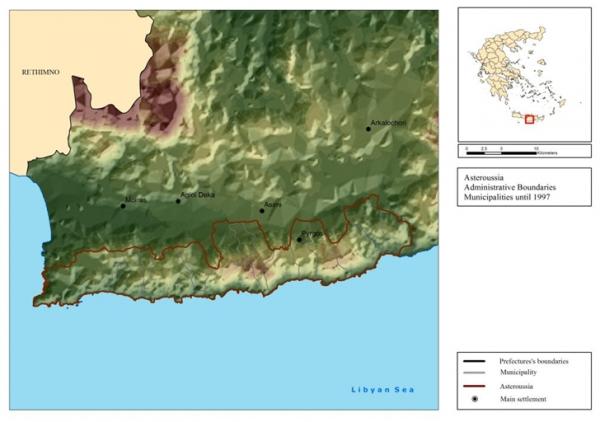

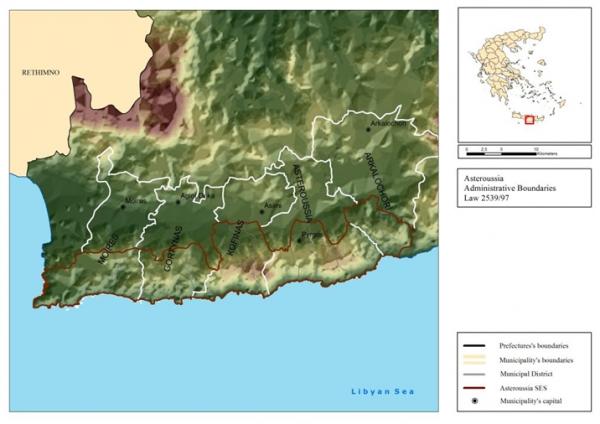

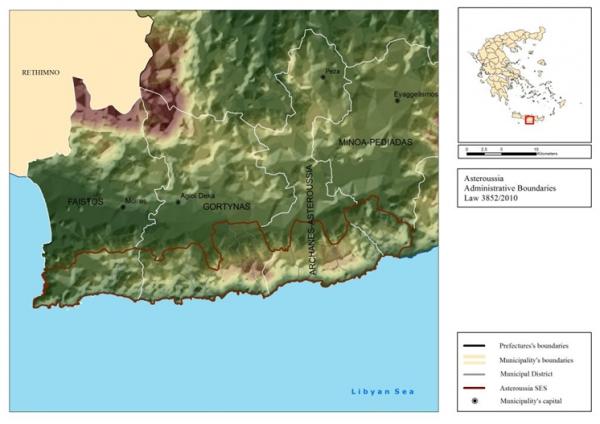

With regard to the first level of self-government (OTA, the local level), municipality (city) and community (rural) jurisdiction limits had remained virtually unchanged since the early 1900s. Administrative reorganization took place in 1997 with grouping of several first level OTA and reducing their number from several thousand to 1034, a change that affected primarily rural communities. Further reform and mergers in 2010 reduced the number of municipalities to 325. The scale of the reform is well exemplified through local government in the study areas. The Messara Valley first level local governments were reduced from 56 to 9 in 1997 and then to 4 in 2010. Asteroussia Mountains first level local governments were reduced from 14 to 5 in 1997 and then to 4 in 2010.