Policy context

Spatial planning policy

| Authors: | Eleni Briassoulis, Alexandros Kandelapas |

| Coordinating authors: | Constantinos Kosmas, Ruta Landgrebe, Sandra Nauman |

| Editors: | Alexandros Kandelapas, Jane Brandt |

Editor's note 3Jul14: Sources D142-3 and D242-4.

Implementation

Spatial planning policy has suffered from weaknesses both in policy formulation at the national level and in implementation. On the one hand, the Greek constitution and several laws have attempted to institute land use and spatial planning regulations and, on the other, the economic growth imperative and weak administrative structures have undermined most attempts to organise economic activity in space.

Goals of spatial planning policy

| Goals of Spatial Planning Policy (L. 2742/1999 on Spatial Planning and Sust. Development) |

Goals of Urban Planning Policy (Law 2508/1997 on Sust. Urban Development) |

|

|

Formal actors implementing spatial planning policy at the study site level are local spatial planning offices and the Regional Directorate for the Environment and Planning.

Local spatial planning until 2010 was the competence of the Heraklion prefectural government that oversaw three branch offices in Heraklion, Moires and Kastelli, of which the last two cover the study site in its entirety. The main function of these offices has been the issuing of building permits, with few long- term planning initiatives at the local or prefectural level.

Although the 1997 and 1999 administrative and legislative reforms gave new impetus to spatial planning at the regional level, the preparation of the regional plans was carried out centrally by the Department of Planning of the Ministry for Environment, Planning and Public Works (reformed in 2009 as the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change, YPEKA).

Policy recipients are, by definition, either formal or informal actors in spatial planning policy. Recipients include private individuals and investors (companies or individuals). The role of consultants, mainly (civil) engineers, in preparing dossiers for building permits is particularly strong. A variety of organised interests and lobbies is also active in spatial planning although the centralised nature of spatial planning policy.

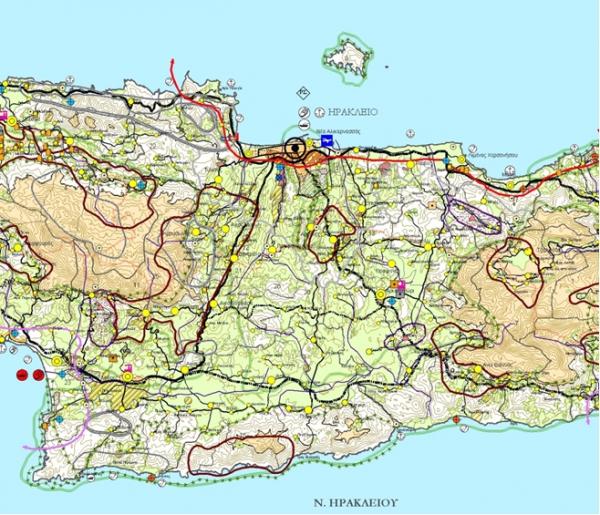

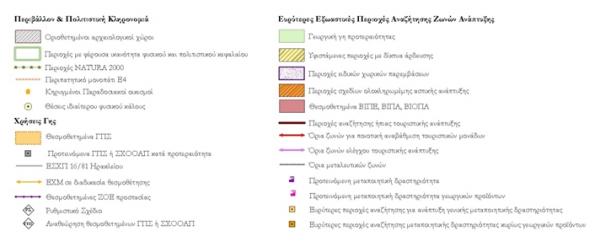

The (national) General Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development (2008) provides general spatial planning guidance documents for the whole country. Its provisions with regard to Crete and the study site in particular include:

- A recognition of a north/south polarization with regard to growth in Crete, with the northern coast being far more developed and the central/southern parts (including the study site) lagging behind and exhibiting a dependence on the urban centers in the north.

- A recognition of Messara as prime agricultural land under threat by scattered building activity throughout its territory.

- The General Framework generally downplays the role of agriculture as a national priority and concentrates instead on transport, energy and telecommunications.

The Regional Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development (2003) characterises the study site as "an area with significant natural and cultural capital".

At the national level, the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change (YPEKA) also prepares Special Frameworks for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development that concern sectors of the economy. Of particular relevance to the study site are Special Frameworks for Renewable Energy Sources (2008) and Tourism (2009). These regulatory instruments are clearly growth-driven and contain provisions which might have dramatic impacts upon land use. Essentially they permit the simultaneous development of tourism and renewables throughout, with the exception of designated archaeological areas and NATURA2000 sites under presidential protection of which there are none in the study site.

The General, Sectoral, and Regional Frameworks provide general guidance, which then has to be ‘translated’ into detailed spatial planning directions through appropriate General Town Plan (GPS) and Plan of Spatial Organisation for and Settlements and Open Cities (SHOOAP). However, only a small fraction of the territory of the study site is covered by such plans (Moires, 1997; Tympaki, 2010; Zaros, 2012). In the rest of the study sites, no spatial or land-use plans have been or are being prepared or implemented. A result of the lack of planning is the proliferation of productive units and to some extent housing and photovoltaic installations throughout prime agricultural land.

In addition to the above, during interviews at the study site, the respondents attributed the weaknesses of the regional and local spatial planning implementation to the following factors:

- lack of political will to undertake and enforce spatial planning;

- lack of coordination between sectoral policies and (horizontal) spatial planning, exemplified in the conflicting and maximalist provisions included in different Special Frameworks and also in poor communication between relevant department;

- in the absence of spatial planning at the lower level, and with weak administrative structures, licensing is done on an ad-hoc basis and generally interpreting the regional framework as non-binding.

Impacts

Specific spatial planning policy instruments have had little impact, as they have been poorly implemented or not implemented at all. Where frameworks exist, impacts are hard to analyse due to conflicting provisions, primarily between the regional framework of Crete (and to some extent the general national framework) and the renewable energy framework. The former designates Messara as primarily agricultural land while the latter opens up all agricultural land to renewable energy development. However, while solar energy installations (photovoltaic cells) are replacing olive groves, it would be far-fetched to attribute this to the Renewables Spatial Planning framework. On the contrary, it seems reflect other government policies and decisions, such as investment incentives and high feed-in tariffs, as well as prevalent market forces. In this context, one may also note the absence of a spatial sectoral framework for agriculture, as the sector has not gained the same priority at the national political scene.

The impact of non-implementation is obvious in other cases:

- Pre-2003 lack of GSP/SHOAAP plans resulted in dispersal of building activity in agricultural and coastal space, that produced a general sprawl along the main roads and the coastal zone.

- Post-2003 lack of GSP/SHOAAP plans reflect reluctance to observe the regional guidelines, with regard to prime agricultural land. In the absence of the latter, the previous laissez faire situation continues, driven by market forces. While pre-2008 tourism had been the main force, it has since been replaced by solar energy projects.

- Lack of implementation of the main instruments available (listing of settlements, land characterisation as productive) reinforces the dynamic for land-use change from farming to residential, tourism, and to some extent, industrial development.

Effectiveness

While the study sites do retain much of their natural beauty (goal 1), this is not necessarily attributable to the law: where commercial pressure does exist, for example along the coast, development proceeds irrespective of other considerations. The lack of effectiveness in this respect is facilitated by conflicting provisions at different levels of planning as well as the general reluctance to adopt land-use regulation at the municipal level. Although Greece, Crete, and Messara have grown rapidly during the last 30 years (goal 2), it is debatable whether this dynamic has been "strengthened" by provisions of spatial planning policy. In fact, general non-implementation of the policy objectives would point to a dissociation between growth and formal spatial planning instruments.

The effectiveness of the policy has also been extremely limited, or non-existent, particularly with regard to "restraining unregulated building" or "control of land-use". Overall, the policies have been quite effective in achieving "covert" goals, such as continuation of non-planning. In a general framework of weak administrative structures, the policy remains practically non-enforced.