Policy context

Agricultural/rural (development) policy

| Authors: | Eleni Briassoulis, Alexandros Kandelapas |

| Coordinating authors: | Constantinos Kosmas, Ruta Landgrebe, Sandra Nauman |

| Editors: | Alexandros Kandelapas, Jane Brandt |

Editor's note 3Jul14: Sources D142-3 and D242-4.

Implementation

Agricultural and rural development is a primarily European policy, designed at the EU level. Implementation of the policy remains largely in the hands of the Ministry of Rural Development and Food (formerly of Agriculture). Local implementation is therefore severely constrained and concerns mainly procedural instruments related to fund administration.

At the study site level, most of the weight of implementation of Pillar I instruments has traditionally been vested with the Department of Agriculture of the Prefecture of Heraklion. which was the regional branch of the Ministry of Agriculture but is now under the elected regional government. Until 1980 (pre-CAP) the Department had a strong technical assistance and programming role in agricultural policy matters. Since 1980, when Greece accessed the EU and the CAP was introduced, the Department assumes the role of intermediary between national authorities and local farmers in the emerging system of subsidy distribution, with its programming role gradually weakened.

CAP reforms led to the institution of OPEKEPE (Payment and Control Agency for EAGF and EARDF). It is directly overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture and operates a local chapter in Heraklion.

Farmer cooperatives have had a formal role in agricultural policy. More than 30 first level cooperatives are active in Messara but, due to their small size and membership they are relatively weak. Unions of cooperatives are significantly more important. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, unions of cooperatives retained a formal role in subsidy distribution. The dual role of cooperatives and their unions as both policy implementers and policy recipients has come under severe criticism and led to widespread disenchantment. When considering cooperatives, it is important to distinguish between "old" and "new" cooperatives. The former, originated in the 1930s, and their close ties with the political system since the 1980s have meant that they have been less market-oriented than many of their members would prefer. This attitude is present among the members of the cooperatives of study communities of Protoria and Gagales that have been interviewed. On the other hand, a new wave of cooperatives, aided by rural development funding, has emerged since the late 1990s, taking the form of producer groups. Although they are not powerful actors in policy implementation, they have dynamism and much clearer contract relationships with their members, devoid of any unionism characteristics.

The main agricultural policy instruments include the Single Area Payment /Single Farm Payment scheme, rural development measures and the Code of Good Agricultural Practice as an instrument of cross- compliance. National policy instruments include, the National Land Cadastre (non-implementation with far-reaching implications).

Assessment of rural policy implementation is constrained by lack of data in the field, particularly with regard to the period from 1980 to 2000. Direct subsidy data remains largely outside the public domain, particularly with regard to smaller geographical units (e.g., municipality). With regard to rural development measures (post 2000), data collection and availability is significantly improved but it is concentrated on the NUTS III level and not the municipality level. In addition, it is further complicated by shifts in fund management: for example from 2000 to 2006 data is "lumped" with regional funds spending.

As a result, analysis has focused on qualitative issues emerging from interviews conducted by LEDDRA researchers in the study site. The main points with regard to implementation of the subsidies in the 1980s and 1990s include the following.

- Direct subsidies have been instrumental in increasing agricultural income and improving living standards of farmers and their families.

- As a general rule, only a fraction of direct subsidies contributed to investment in agricultural holdings in the 1980s and 1990s. While this is in line with the policy's stated objectives (at the EU level), it has to some extent prevented the restructuring and/or modernisation of the agricultural sector.

- Direct subsidies have supported the economy of Heraklion as a whole rather than the agricultural sector of Messara or Asteroussia. Eligibility for subsidies has included thousands of individual land-holders and legal persons (e.g. the church), living outside Messara. This has evolved into a source of considerable friction with farmers and locals. The ability of "outsiders" to obtain income support has also functioned against restructuring through market forces, such as land consolidation.

The introduction of the Single Area Payment/Single Farm Payment since the early 2000s has to increased the pressure on full-time farmers to modernise and, in particular, to seek agricultural income outside the various price guarantee support schemes. This tendency is exemplified by the rapid expansion of intensive greenhouse farming in Messara and, in particular, around the southwest town of Tympaki.

In 2009 decoupled direct subsidies in Crete amounted to €293 million and they were directed to almost 137,000 beneficiaries. As a result, Crete ranks third among the thirteen Greek regions according to subsidies received (13.7% of a total 2.14 billion) and first according to the number of beneficiaries (16.7% of 822,000 beneficiaries). It ranks fourth, however, with regard to the net value of agricultural production (€396 million) and second to last with regard to the ratio of net value over total value (including subsidies): at 57% this ratio is below the national average (62%). Bearing in mind that Messara includes a significant part of market-driven, export oriented farmers occupied in vegetable farming, it becomes clear that the structural problems identified above, as far as Messara is concerned, relate primarily to the production of olives and olive oil.

Rural development instruments have also been primarily financial, originating in the first LEADER Community initiative in 1989. Heraklion was one of the first areas of Greece where a local action group was formed, becoming a testing ground of the local partnership model which constituted a major institutional innovation for the country. This partnership resulted in the formal establishment of the Heraklion Development Agency in 1989 which, along with the Ministry of Agriculture, has been the main implementer of rural development policy in the Messara study site. HDA's first shareholders were 4 communities of northern Herkalion and, through subsequent public offerings, it has expanded to include all municipalities and several agricultural cooperatives

Data availability of EARDF funding improves since 2000 but it is hampered by the lumping together of projects receiving funding under different sources at the regional level. Nevertheless, an exposition of processed data allows one to draw general conclusions with regard to implementation in the region of Crete.

During the period 2000-2006, agricultural infrastructures, including the Faneromeni reservoir within the boundaries of the Messara study site, captured the lion's share of EARDF spending (over €78 million), followed by other infrastructure (roads, settlements etc. over €37 million) and investments in agricultural holdings (almost €17 million). Therefore, rural development policy seems to replicate tendencies already present in regional development policy:

- The construction of large works presents an equilibrium between policy users and implementers. On the other hand, auxiliary activities and measures for operation are often non-implemented (irrigation networks, water management plans).

- Both the "integrated interventions" and "infrastructure for areas lagging behind" categories (totalling almost €50 million) include large parts of road and building construction. Again, these sums are directed to a bloated public works sector without direct relevance to the agricultural economy.

- "Investments in agricultural holdings" have been an important source of support for farmers but not to shepherds (Asteroussia study site)

- "Agri-environmental measures", have constituted only a minor spending category in the region (€2.6 million). This is largely due to lack of familiarity of formal implementers (Ministry of Agriculture and prefectural Departments of Agriculture) as well as of policy recipients (consultants, farmers) with the nature of the interventions.

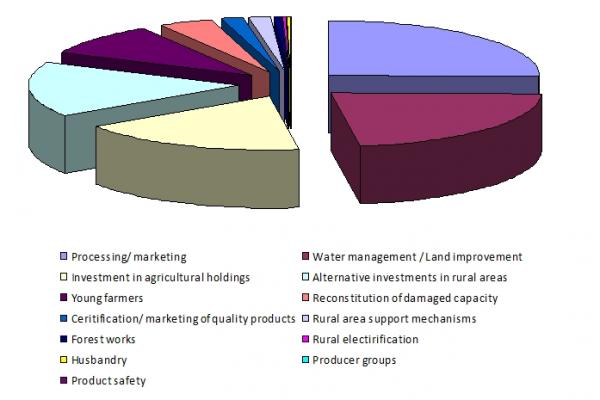

- The dominant spending categories are processing and marketing (almost €48 million), water works (€42 million), investments in agricultural holdings (almost €34 million), alternative investments (e.g. tourism; €31 million) and young farmers (€17 million).

- The absence of agri-environmental measures is almost complete.

- Despite the above, the agricultural profession seems to remain relatively attractive for the prefecture of Heraklion with several thousand farmers entering the profession or modernising. The bulk of relevant spending was directed to Messara and a large portion of funding was ultimately directed to greenhouse expansion.

- By comparison, collective efforts by farmers are generally absent from Heraklion and Messara. Support for setting up producer group measures has been extremely limited, not due to lack of funds but rather due to lack of demand.

EARDF 2000-2006 in Heraklion (excluding roads and settlements)

| Measure | Geographical frame of reference | Measure budget (euro) | Budget in Heraklion prefecture (euro) | % of measure spent in Heraklion |

| Processing/ marketing* | Greece | 1,201,454,494 | 47,805,972 | 4% |

| Water management / Land improvement | Heraklion | 42,001,507 | 42,001,507 | 100% |

| Investment in agricultural holdings* | Crete | 95,030,634 | 33,773,985 | 36% |

| Alternative investments in rural areas | Crete | 170,206,781 | 30,905,708 | 18% |

| Young farmers * | Crete | 39,757,189 | 17,394,227 | 44% |

| Reconstitution of damaged capacity | Greece | 76,003,371 | 7,939,882 | 10% |

| Certification/ marketing of quality products | Greece | 37,195,311 | 3,302,082 | 9% |

| Rural area support mechanisms | Heraklion | 3,185,468 | 3,043,189 | 96% |

| Forestry | Heraklion | 1,057,968 | 1,057,968 | 100% |

| Rural electrification | Heraklion | 648,794 | 648,794 | 100% |

| Husbandry | Greece | 4,080,775 | 230,382 | 6% |

| Producer groups* | Heraklion | 14,288,588 | 114,607 | 1% |

| Product safety | Heraklion | 59,826 | 59,826 | 100% |

| TOTAL | 1,684,970,706 | 188,278,129 |

*Includes commitments made in previous programming period

Source: www.ops.gr, accessed November 12th 2012; processed by the authors

A series of public and private stakeholders (individuals, cooperatives, municipal official) point to a complete absence of inspections, controls and penalties at the farm level. Dossiers and applications are processed in offices in Heraklion and Athens but verification of action taken is extremely limited (cross-compliance requirements with regard to the environment, soil and water).

Agricultural and rural development policy implementation intersects with spatial planning policy and water policy.

Impacts

The most important impact of agricultural policy has been the support of farmers throughout the study site by providing generous income support for agricultural incomes. As a result, it has contributed to the raising of the standard of living as well as the broader regional economy.

A major unforeseen impact of the policy has been the establishment of powerful policy actors at the national, regional and local levels. Their function as intermediaries for subsidy distribution has served at the same time to solidify their position but also to create widespread disillusionment of farmers. This dominant (rentier) position has maximised their political influence as well as a general stagnation vis-a-vis Pillar II reforms and rural development in general.

In the study site, these actors (politicians, cooperatives and the public administration) have also been reluctant to follow CAP reforms, and have actively prevented the implementation of agri-environmental components of rural development policy since 2000. The limited examples of collective action and agri-business development, despite the existence of a critical mass of farmers, are such a case.

In this context, farmers (Messara) and shepherds (Asteroussia) have been unable to capitalise on traditional farming practices: while the EU has focused on extensification and lower input and impact agriculture, the sector in Messara has undergone drastic intensification, fuelled by financial support for new investment primarily greenhouses.

At the individual holding level, lack of professional training and education coupled with ample finance has led to unsustainable growth. Farmers have modernised and relied more on inputs (fertilisers, seeds, pesticides), largely due the availability of cash. However, as primary resources (soil and water) dwindle and the prices of supplies rise, individual farmers are extremely exposed and may lack survival options.

Nevertheless, the separation of the impacts this policy from other trade and economic policies is almost impossible. Farmers have benefited from the first stage of EEC integration through falling supply and machinery prices, credit availability as well as a broader market for agricultural products. On the other hand, since 2000, they have been particularly exposed to global trade and price fluctuations, which are impossible to deal with at the level of the small Messara holding.

The small level of holdings has also been a decisive factor in preventing policy implementation of other policies requiring coordination and management, most notably water policy.

Effectiveness

Price support and subsidies have contributed to the achievement of all CAP objectives since the 1980s when they were first implemented. Standards of living have generally risen, markets have been stable and agricultural products have generally reached consumers without problems.

The CAP contributed to increasing agricultural productivity through dramatic increases in inputs (machinery, fertilizers etc.) to which substantial sums of subsidies were directed. However, productivity is also partially the result of specialisation advocated by national policies in the 1970s. These changes were in turn finalised through the subsidy system.

CAP reforms since 2000 have widened and replaced the policy's objectives.

In Messara, the introduction of rural development policy has contributed to the competitiveness objective through the introduction of support for new investment, particularly greenhouses, which now dominate production and local revenue around the Tympaki area. On the other hand, broader restructuring and collective efforts have been limited. Little modernisation has taken place in the Asteroussia study site through rural development instruments.

The second objective to be implemented through agri-environmental measures has largely eluded the area. The construction of the Faneromeni dam may be seen to contribute in that direction, however, as the dam was only recently completed its contribution to improving the environment remains to be seen. In fact, one could argue that the environment objective has been directly undermined by the first objective, by fuelling water use, high-input agricultural, and the proliferation of agricultural waste (plastic), particularly in the Messara study site.

The policy has been more effective with regard to the third objective by providing support for local businesses (arts and crafts, bed and breakfasts) and municipalities.

The decoupling reform has led to significant reductions in farmers' income and undermined stability. This process has been augmented by the reluctance of the administration and key actors (cooperatives) to prepare for the reform. Overall, the general stance of denial and aggressive support for "business as usual" left the sector exposed at the lower level (individual farmers and olive grove owners). Although, the policy may be seen as effective with regard to greenhouse horticultural produce which has a strong dynamic, the olive sector in Messara and stockbreeding in Asteroussia have been particularly hit by the reform

The sustainability objectives (rural development, health check) remain largely elusive.