Policy context

Water policy

| Authors: | Eleni Briassoulis, Alexandros Kandelapas |

| Coordinating authors: | Constantinos Kosmas, Ruta Landgrebe, Sandra Nauman |

| Editors: | Alexandros Kandelapas, Jane Brandt |

Editor's note 3Jul14: Sources D142-3 and D242-4.

Implementation

Historically, the main national actors with regard to water policy have been the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Development. Their role in general policy design has been limited. The Crete Regional Water Directorate has been assigned with regional water management and monitoring since 1987. Although throughout Greece, Regional Water Directorates have been seen as generally underperforming and limited their role to the issuing of water use and water works licenses, the Crete Regional Directorate has been particularly extrovert in its attempt to tackle broader water management issues through particular measures as well as through its participation in international projects.

The recent transposition of the EU Water Framework Directive foresees the formation of a Regional Water Committee (consultation body) which has not yet been activated in Crete.

The various Agricultural Departments (prefectural) of Crete have carried out a large number of studies for irrigation and water storage works which have to a very large extent dominated water policy in the island. Since the 1990s these works have been constructed by the Public Works Directorate of the Region of Crete.

Since the late-2000s, the National Special Secretariat for Water has been extremely active in the preparation of water management plans on behalf of the regions. Nevertheless, in the case of Crete the process has been stalled and no draft plan is in consultation as is the case in the rest of the country. This is attributed to internal bureaucratic reasons within the Ministry of Environment.

Locally, urban water provision and pricing is regulated by the municipalities or companies under municipal control (Municipal Water and Sewage Companies-DEYA). Two DEYAs operate in the study sites (Messara only) in the Municipality Minoa-Pediados and the Municipality of Phaestos. Municipalities operate wells and water distribution networks, as well as sewage facilities, where they exist.

Municipalities also oversee the operation of TOEBs (Local Organisation of Land Improvement). TOEBs manage and price local irrigation water on behalf of farmers, with the latter’s participation. Messara includes 4 TOEs based in Moires, Tympaki, Pompia, and Ini.

A large number of private wells exist in the area, both legally and illegally. In this case, the user, generally either a farmer or a hotelier, may enter into an unofficial arrangement to sell water (e.g. to neighbours).

Informal actors in water policy are local engineers, contractors, and politicians lobbying for public works. Their influence partly explains the dominance of water works on the public agenda as opposed to water management schemes. The Region of Crete has seen the construction of several dams and reservoirs during the last 20 years, driven by the availability of Structural Funds financing.

While most actors tend to be formal, their relationship may assume informal characteristics. For example, along the Messara coast, significant tension exists between farmers and locals, particularly during the summer months, when demand is high for tourism and irrigation. Given that the law and subsequent municipal council decisions prioritise the provision of potable water, farmers may resort to water theft from the public water network.

Pricing for water is another case where informal relationships may come into play. In the first instance, prices may be set at low levels to ease political pressure upon municipal officials. Furthermore, bill and fine payments may become the object of clientelist relationships with officials turning the other way towards widespread non-payment.

The main water policy instruments implemented at the Messara study site are water monitoring programmes, the water use and water works license, reservoir construction and restrictive measures. Instruments not implemented include a water management plans (either local or regional) with regulatory status and nitrate pollution prevention.

Several water monitoring networks have been in place in the Region of Crete since the 1980s, providing adequate information with regard to water quality and quantity. The Water Directorate has been extremely proactive in attempting to regulate water use, including the preparation of a regional water management plan in the late 1990s. Although this draft plan is one of the few prepared in the country, it was never formally adopted by the regional government. At the moment, Crete in now the only region without a regional water plan.

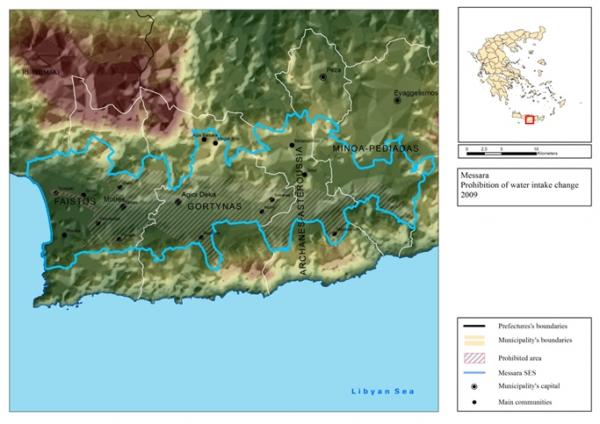

Two decisions have been issued by the Regional Secretary bannning new groundwater drilling installations in large parts of the island and extensive parts of the Messara valley, covering approximately 43% of its area. It has to be noted however that the Tympaki area, where pressure is most intense, remains outside the scope of the restriction decision.

The exact number of wells in the area remains unknown, despite two countrywide attempts at a census of water (use) rights. In 2010, all water use license holders were required to re-register their licenses or they would lose them. At the time of writing, this process was still in progress.

With regard to implementation, it must also be noted that there is no established procedure for the verification of actual use by each license holder. Reports of overuse abound.

Several reservoirs serve the Messara study site and several more are planned for construction. Reservoir construction has taken place since the 1990s, driven by the availability of EU structural funds.

Water pricing is implemented by TOEBs or Municipalities albeit not without problems. Average water price in Messara is currently at €0.18 /m³, well below TOEBs or municipalities management costs or cost recovery thresholds, with irrigation being financed by public municipal resources. This is confirmed by interviews with municipal civil servants. Despite the construction of the large Faneromeni reservoir, management and pricing continues to take place at the municipal department level without any overall management structure.

With regard to nitrates, Messara is not on the List of Vulnerable Zones and no special water pollution prevention and control programmes are in place, despite extensive application of nitrogen fertilizers. With regard to industrial wastewater, water policy implementation is streamlined through the relevant provisions of horizontal environmental policy. Upper limits of water to be used in irrigation exist both in national laws and in regional regulations presented above. Nevertheless, checks and controls on the ground are virtually non-existent. Where transgressions are noted by fellow farmers they tend to be dealt with in an informal fashion primarily through recourse to political and family networks. Fines and other sanctions for water use and pollution are also non-existent.

Impacts

Water use instruments (licenses) have overshadowed management instruments (planning, coordination, pricing, conservation). The latter are completely absent in the study sites. Water scarcity in Messara and elsewhere may be seen as direct impact of the partial implementation of policy instruments in the period after 1987, also coupled with other formal policies (environmental licensing) and agriculture. Water extraction has also been driven by funding availability, most of it originating from EU sources (agricultural holdings, hotels, municipalities).

Despite calls for control from scientists and the civil service, political willingness to accept any sort of local regulation on water use has been remarkable, but understandable: tourism and agriculture are the main sources of income for the study site. Limits upon water use could possibly affect product quality for both sectors. However, the region's decision to prohibit all new wells in most parts of Messara is indicative of the gravity of the situation and the problems of the lack of coordination. Implementation at the lower level faces the same problems, with considerable reluctance to engage in management and conservation.

Effectiveness

The formal process for obtaining water use licensing (1987), "democratised" water use by generally making groundwater extraction available to all. This has certainly been the case in Messara. On the other hand, management plans for the country and the regions, although formally foreseen, were never prepared.

Law 3199/2003 clearly includes "the protection and management of inland surface waters and groundwater" as its central goal and points also to the general objectives of the EU Water Framework Directive (provision of sufficient supply of good quality water, significant reduction in pollution, protection of territorial and marine waters etc.)

The lack of policy effectiveness is generally evident, most notably in aquifer depletion in the summer months and subsequent water conflicts being characteristics of the current water situation.

Nitrate pollution policy remains non-implemented in Messara, as there has been a central political decision to exclude olive groves from consideration for inclusion in the sensitive areas list. The policy has been non-effective with regard to its stated goal of "protect[ing] of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources". Such sources abound in Messara whether in olive grove management or horticultural production along the coastal plain.